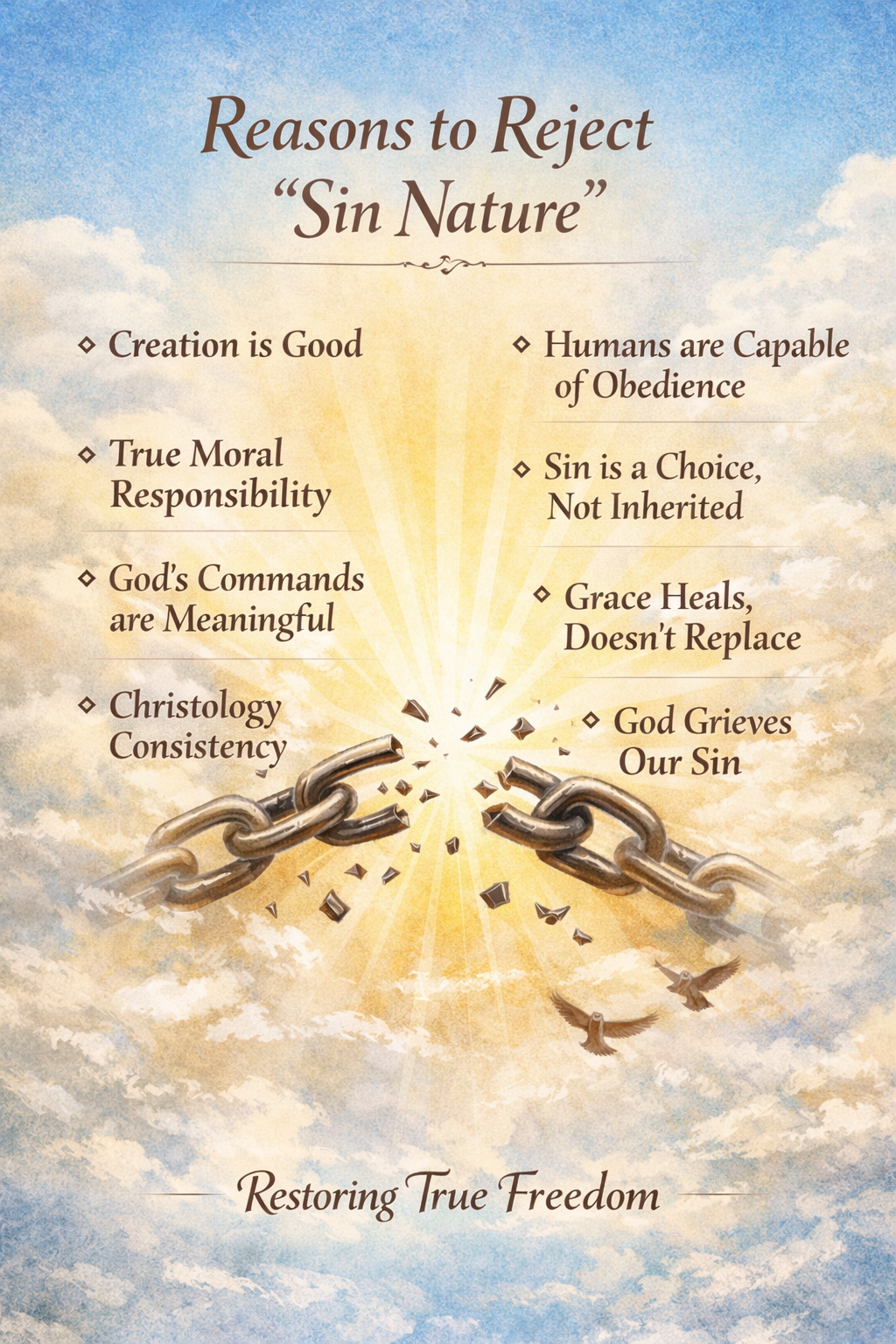

Reasons to Reject Traditional “Sin Nature”

By Dr. Peter A. Kerr

Whereas the article on how the image of God is not marred is more Scriptural, this article is more logical, but it seems like many people will push back against a denial of “sin nature” and so more reasons may be required. This article first lists the supposed benefits of sin nature, then explains how they are unnecessary, then lists the benefits of doing away with a tradition that finds little (or no) support in properly exegeted Scripture.

First, sin nature has explanatory power by clearly answering “why” all people sin. Second, it protects against moralism or the notion that sin is merely a bad habit that can be dealt with through education. Third, it may be humbling to accept and so serve to protect people from self-righteousness, and fourth it may therefore make people realize they rely upon God’s grace. Finally, It helps people explain/justify their internal struggle with sin by making sin seem like an outside or core persuasive force.

Everything the doctrine does well can be preserved without saying humans are ontologically flawed at birth:

• The universality of sin can be affirmed as historical and existential, not metaphysical.

• Moral seriousness can be preserved without denying real capacity for holiness.

• Grace can remain essential as healing and participation rather than re-engineering.

• Humility can be grounded in shared failure rather than shared defect.

• Inner conflict can be understood as misdirected freedom rather than broken being, and the feeling of an external force easily fits into Scriptures teaching that there are real demons who tempt humans.

So what are some reasons why we should give the doctrine a second look of scrutiny?

First, ontological defect collapses the distinction between creation and corruption.

Scripture consistently treats creation as God’s good work and sin as a later intrusion, not a feature baked into human being itself. If humans are born ontologically flawed, then the defect must originate either in God’s creative act or be transmitted as a quasi-substance from another creature. The first implicates God as the author of a damaged nature; the second introduces a metaphysics of inherited corruption that Scripture never explains or names. God does not require a “blueprint” or “mold” to make humans, and the Bible is silent about such industry-inspired speculations. Biblical language instead speaks of corruption spreading through practice, desire, imitation, and distorted worship, not through ontology itself.

Second, inherited defect undermines personal moral responsibility.

Responsibility presupposes the real ability to respond otherwise. If a person sins because they are constitutionally unable not to sin, then culpability becomes attenuated. Judgment turns into diagnosis, and repentance becomes incoherent. Scripture, however, consistently addresses people as genuinely answerable agents: “choose,” “turn,” “repent,” “do not harden your hearts.” These imperatives only make sense if sin arises from willing misalignment rather than metaphysical incapacity.

Third, ontological flaw makes divine commands morally opaque.

God repeatedly commands holiness, obedience, trust, and love without ever qualifying those commands by saying, “You cannot actually do this, but I require it anyway.” If humans are born unable to obey even in principle, then divine law functions less as moral guidance and more as a mechanism of exposure. That logic quietly shifts God from teacher and healer to prosecutor. We should resist this by affirming that commands presuppose real capacity, even when that capacity is routinely misused.

Fourth, the doctrine of sin becomes indistinguishable from the doctrine of creation.

If every human act inevitably issues in sin because of a defective nature, then sin is no longer a tragic contradiction of our telos; it becomes the predictable expression of it. Scripture never speaks this way. Sin is always framed as disorder, deviation, exchange, suppression, or turning aside—language that only works if something good and rightly ordered was present to begin with.

The Old Testament nowhere supports an evil nature in humanity. Jewish wisdom literature and rabbinic tradition consistently affirm the fundamental goodness of humanity as created by God, while also maintaining a sober realism about human moral struggle. Judaism does not teach an ontological corruption of human nature at birth.

Fifth, ontological defect destabilizes Christology.

Any account that says humans sin because of what they are by nature must then explain why Christ, who shares our nature fully, does not sin. Historically, this forces theologians either to exempt Christ from ordinary humanity or to redefine “nature” so narrowly that it no longer does explanatory work. The New Testament avoids this dilemma by locating temptation and obedience within real human freedom. Christ resists sin not because He lacks our humanity, but because He perfectly loves and trusts the Father.

Sixth, it distorts the meaning of grace.

Grace, in Scripture, heals, elevates, restores, and perfects. It does not replace a defective ontology with a new one as though creation failed the first time. If humans are ontologically broken, grace becomes less like medicine and more like re-engineering. Grace is relational participation in divine life, not ontological repair of a botched design.

Seventh, it conflicts with the biblical pattern of divine grief rather than divine surprise.

God is portrayed as grieved, disappointed, and pained by human sin, not as encountering the inevitable outcome of a nature He Himself rendered incapable of obedience. Grief presupposes violated expectation, not fulfilled necessity. The prophets, the Psalms, and the ministry of Jesus all assume humanity could have loved differently—and still can.

Eighth, it introduces unnecessary metaphysical speculation.

Scripture never explicitly teaches humans are born ontologically damaged. What it does teach clearly is that all eventually sin. Moving from universality of sin to defect of being is an inference, not a revelation. Theological restraint is needed: we should affirm everything Scripture affirms, but we do not need to add metaphysical mechanisms Scripture never names.

Finally, and maybe most importantly, it weakens hope rather than strengthening it.

If sin flows inevitably from who we are, then holiness will always feel artificial, strained, or alien. If sin flows from misdirected freedom, then holiness is the fulfillment of what we were always meant to be. The New Testament vision of sanctification makes sense only under the second account. We are not becoming something foreign to ourselves; we are becoming fully human at last.

The risk of retaining a doctrine of “sin nature” is not primarily theoretical but cumulative. Over time, it subtly trains believers to expect sin more readily than holiness, to interpret moral failure as fate rather than tragedy, and to regard obedience as something unnatural to being human. What begins as pastoral realism can quietly harden into theological resignation.

The converging reasons outlined above therefore matter. Rejecting an ontological flaw at birth does not soften the doctrine of sin; it intensifies it by locating guilt precisely where Scripture does—in the will’s tragic refusal of love rather than in created being itself. We can retain the realism of struggling with sin, the recognition of humility, and humanity’s deep need for grace—but ground them in wounded freedom rather than in damaged being. This protects God’s goodness, preserves genuine moral responsibility, safeguards Christology, and allows grace to be what it is meant to be: not the repair of a failed creation, but God’s holy love drawing willing creatures into life.

A Scriptural Boundary Worth Keeping

Scripture is unambiguous that all people will sin (Rom. 3:23). It also presents Adam not as a biological transmitter of guilt or corruption, but as an exemplar whose disobedience inaugurates a world in which sin spreads historically and relationally. The Bible further acknowledges generational consequences of sin—spoken of as extending to the third and fourth generation (Exod. 20:5)—without ever teaching an inherited ontological defect passed from Adam to all humanity.

At this point, it is tempting to move beyond Scripture by positing a “sin nature” implanted in Adam and transmitted to every human being. That move may feel explanatory, but it goes beyond what Scripture actually says. When a theological inference does not cohere with the full witness of Scripture—especially when it complicates Christology, weakens moral responsibility, or implies a flaw in God’s creative work—it should be resisted.

The doctrine of original sin, as an inherited defect of nature, fails this test. Scripture affirms universal sin and generational consequence, but it does not require a corrupted human essence at birth. Holding the biblical line preserves both God’s goodness and Christ’s full, faithful humanity.

The position here is that the first sin is not compelled by nature, defect, or inherited propensity; it is freely chosen. Thereafter our nature of sinning is birthed and we have what Scripture calls “the flesh.” This is not a flaw in the image of God, but rather is the entrenched pattern of disordered desire, habituated resistance, and weakened trust that sin produces over time. Because it entails relational rupture, a person’s image of God is tarnished. Pain often enters the picture as a diagnostic to indicate something is wrong and needs repair.

Sin naturally leads to more sin in increasing intensity. Distortion deepens, and divine grace must precede and awaken our response. Prevenient grace, then, is not the repair of broken ontology, but God’s merciful, initiating love toward enslaved wills—calling, illuminating, and enabling repentance and faith without coercion. It does not re-engineer human nature; it restores our intended ability to be holy as God is holy. Holiness is the natural position of humanity in relationship with God — sin is the unnatural position of separation caused by willful sin.