God’s Wrath: When Holiness Meets Entrenched Evil

by Dr. Peter A. Kerr

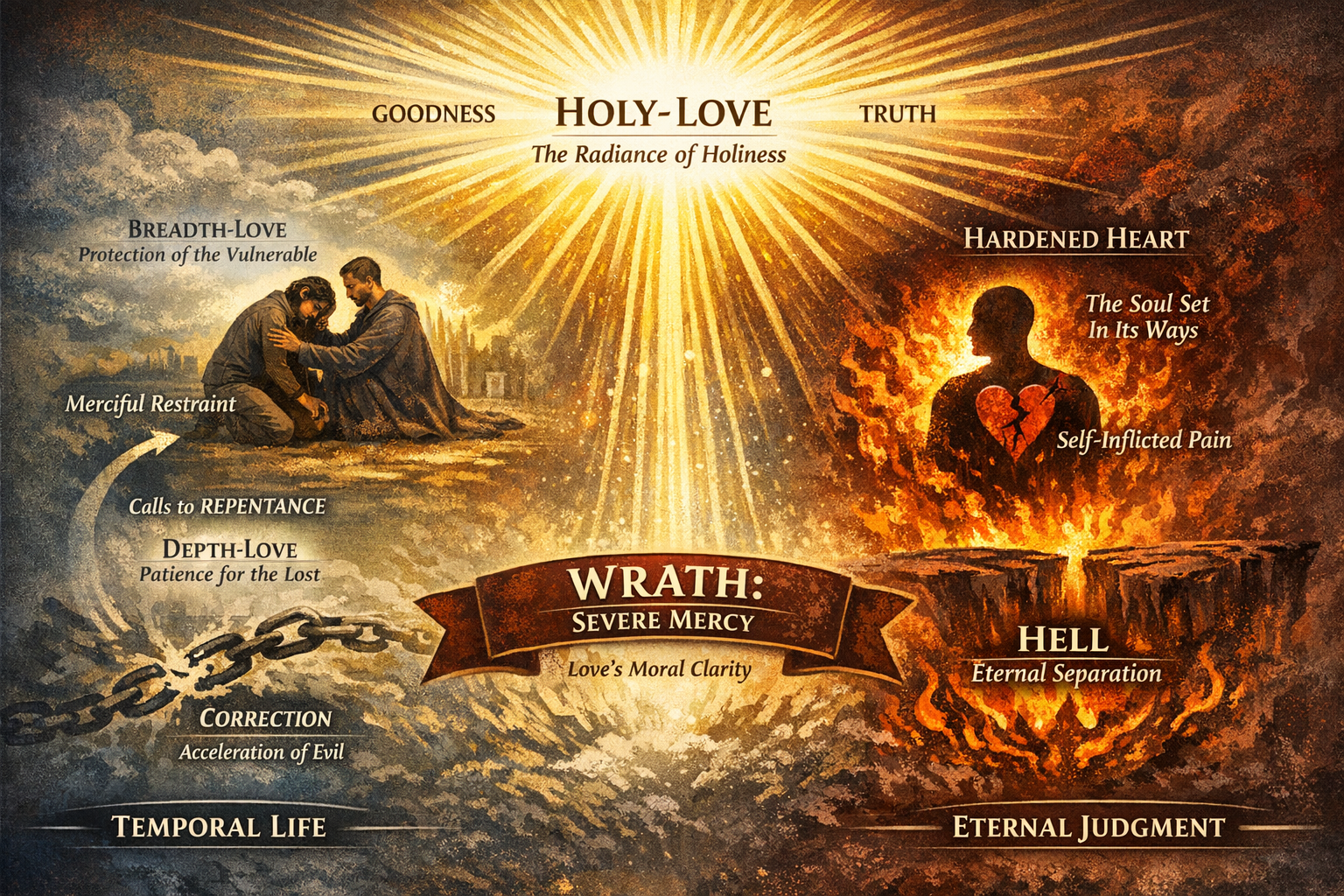

The divine nature is one radiant holiness expressed through the modalities of the Father’s goodness, the Son’s truth, and the Spirit’s love. These are not three ingredients but three personal expressions of the one plenitude. Divine action cannot arise from conflicting motives. Wrath must be understood as emerging from the same diffusive love that creates, the same faithful truth that redeems, and the same goodness that upholds all things.

Holiness is best understood as the simple fullness of goodness, truth, and love—a radiant unity we may call holy-love. Because this unity is undivided, every divine action arises from the same superabundant source. Wrath, therefore, is not a competing attribute or a temporary departure from love, but holy-love’s morally fitting response to destructive evil.

Love protects what is vulnerable, reveals truth, and exposes what corrodes communion. God must love both victim and perpetrator for as long as healing remains possible, yet when a beloved will becomes harmful to itself and to others, love does what love must do. Scripture does not portray God as oscillating between tenderness and fury, as though justice and mercy were rival impulses. The divine motive never shifts. The same radiant plenitude that delights the receptive soul becomes painful to the resistant one, not because God changes, but because the distorted mirror can no longer bear the light that was meant to heal it. Love is intended to be reflected; when it is resisted and absorbed inwardly, it becomes heat—experienced as pain and manifest as sin.

Heat radiates to hurt others. Society is full of heat being radiated. All pain and sin are due to human choices. The very earth and time itself was damaged at the Fall of Adam. Natural disasters occur with increasing frequency because human greed and excesses further pollute creation’s initial goodness.

Wrath intensifies precisely where evil threatens to destroy. It is the lioness defending her cubs, the surgeon cutting to save, the light revealing what hides in shadows. The severity does not reflect a withdrawal of love but its heightened form when confronted with willful harm. However, God balances love for the afflicted (breadth-love) with His love for the “afflictor” (depth-love). This explains Scripture’s pattern: God is repeatedly described as slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. The slowness reflects depth-love’s patience; the confrontation reflects breadth-love’s protective goodness.

Love for Both Victim and Perpetrator

God always loves both victim and perpetrator. When God confronts evil, He is not choosing sides in a zero-sum contest. He refuses to abandon the wounded and He refuses to abandon the one who wounds. The Christian who is strong in the Lord suffers the most, because that suffering allows God to continue in merciful invitation to the perpetrator. This can only be empowered by the Spirit as God and other Christians bear our burdens with us, and it is enacted by Jesus’ teaching to turn the cheek and love the enemy.

This is not to say victims should always continue to accept pain. Abused wives should leave their husbands out of love for themselves (protection) as well as love for the husband (reduce the evil he can enact).

In situations where the victim is called to stay and take the pain, God joins the pain, absorbs the pain, transforms the affront into reflected holy-love. God protects, rescues, and emboldens the creature to stand up to further injustice. When the victim can no longer choose holy-love, or when the perpetrator has fully committed to only evil, God moves to against the perpetrator.

For the victim, we know God also works all things for the good of those who love Him and are called according to His purposes (Rom 8:28). This means our love for God allows Him to transform all evil directed at us into something that ultimately blesses us. Many Christians fail to realize this blessing as they do not love Him, trust Him, and they refuse to forgive. Forgiveness and loving the enemy often become the mechanisms of God’s transforming what was meant for evil into His good blessing.

Wrath As Love for the Perpetrator

God safeguards the reality of creaturely freedom because love desires genuine repentance and restored/initial communion. Yet freedom is never unbounded autonomy. It is always freedom within the arena of creation, and within shared interior space constituted by the Spirit’s indwelling presence. Every act—holy or wicked—occurs within this space. While the Spirit personally indwells the believer (the Body of Christ is His Temple), God is omnipresent and so He is also within the unbeliever who often denies and rejects the Spirit’s voice of conscience.

For the perpetrator, wrath is first restraint, exposure, and limitation. God often throws obstacles in the way of people who want to do evil, affording them the chance to rethink the act. He even uses creation (the dance floor in the dance analogy) to arrest the descent into deeper self-corruption by getting the person caught or exposed. Every sinful destructive act further distorts the mirror of the soul, and it is often a slippery slope as sin begets more and more damaging sin. To love the victim, God often has them caught/arrested/restrained.

God interrupts the steep descent, preventing deeper collapse and offering the clarity that can open the way back. This first act of wrath is a doubled mercy as it defends the vulnerable and limits the self-destruction of the offender. It is not vengeance so much as holy-love resisting the further corrosion of a soul and protecting people from harming themselves and others.

Hardening of the Heart: Acceleration Rather Than Manipulation

At times, a will becomes so bent toward evil that permitting its prolonged expression would multiply devastation. In such cases, God does not manipulate the will or inject evil into the soul; rather, He accelerates the trajectory already chosen in order to limit the harm that evil can actualize. What is shortened is not the capacity for repentance, but the duration in which evil is allowed to mature before reaching settled conviction. Even in hardening, the divine motive remains unchanged: the flourishing and protection of all creatures involved.

Divine hardening is therefore neither coercion nor the override of a receptive will (Jas 1:13). It is the morally fitting judgment upon a willed evil, whereby God withdraws softening influences and allows the bent will to reach resolution more quickly (Rom 9:17–18). The nature of concrete is to harden when left alone; similarly, God simply allows the sinner’s heart to harden rather than opposing it. This acceleration brings the perpetrator to a decisive posture—one that prompts divine intervention to protect victims—without violating freedom or dignity (Prov 16:4). While repentance remains possible for as long as the will is not finally closed (Isa 55:6–7), increasing sin bends the soul further, narrowing the will’s openness until evil becomes firmly chosen (Heb 3:12–13).

Hardening, then, is a just response to prior evil, not its cause. By hastening the arrival of judgment, God limits the spread of harm and relieves those under threat. What is removed is not the possibility of repentance, but the prolonged delay that would allow further destruction. Even the offender is given a mercy as he or she is not allowed to perpetrate more evil and thereby harm themselves. The will is never forced; the trajectory is simply allowed to reach its end more swiftly.

This acceleration serves multiple goods. It protects potential victims by bringing evil to a head before it spreads further and more painfully (Prov 11:21). It limits the perpetrator’s deeper self-corruption (and so meriting more punishment) by shortening the sequence of wicked acts (Eccl 8:11–13). It reveals truth by making the heart’s posture unmistakably clear (Luke 12:2–3), and issues a clarion call to repentance (Acts 17:30). In this way, hardening is a severe mercy—holy-love acting with moral clarity where prolonged indulgence would inflict greater harm on both victim and perpetrator alike (Heb 12:29).

Wrath on Earth and Wrath Beyond Death

Within temporal life, wrath is encountered primarily as the restraint of evil, the exposure of injustice, and the protection of the vulnerable. It remains dynamic, relational, and oriented toward repentance. Earthly wrath is thus largely medicinal, corrective, and revelatory. It seeks to limit harm, call the perpetrator to truth, and restore moral order. In extreme cases, this restraint may even take the form of the perpetrator’s death, which—severe as it is—can constitute a final mercy by preventing further devastation to others and deeper corruption of the self that merits punishment in the afterlife.

Beyond death, however, the mode of existence shifts from becoming to being. The soul receives its spiritual body and is fixed in its orientation. Yet the object encountered does not change: the unceasing radiance of God’s holy-love. Death cannot interrupt divine love; God remains present even beyond judgment. What changes is the soul’s capacity to receive that presence. A will bent away from love now encounters holy-love not as healing light but as searing heat—an experience that endures precisely because the soul’s posture has become settled.

The pain of Hell, therefore, is not externally inflicted as a punishment imposed from without. It is the unrepentant soul’s enduring misinterpretation of the same holy-love that always sought its restoration. After the Day of Judgment, the mirror of the soul is set in its final orientation. To the degree that love has been resisted, absorbed inwardly, and contorted into self-regard, the soul experiences that love as pain. We are, in the end, the summation of our freely chosen loves. Choices that are selfish, violent, or closed to repentance shape the soul itself, forming a capacity for suffering that is perfectly attuned to what the person has become.

Wrath, in this eschatological sense, is not merely punitive, though it is fully retributive. Justice is rendered not through divine hostility, but through the unwavering consistency of divine holiness. God does not send hate; the creature’s distorted posture renders God’s radiance unbearable. The source of pain lies not in God’s disposition but in the soul’s orientation toward that disposition.

There is not a definitive biblical position on whether the suffering of such souls is everlasting or whether it endures until justice is fulfilled and the soul is finally extinguished…or a hybrid that depends on the extremity of love’s rejection. Scripture appears capable of sustaining either reading. The notion that the soul is naturally immortal owes more to Greek philosophical inheritance, mediated through figures such as Augustine, than to explicit biblical teaching.

A coherent reading of Scripture suggests this is not a forced either–or. Jesus repeatedly teaches judgment is proportionate, involving degrees of severity rather than a single undifferentiated fate (Luke 12:47–48; Matt 11:22–24). Scripture also employs two distinct but complementary vocabularies of judgment: some passages unmistakably depict ongoing conscious torment (Rev 14:10–11; 20:10), while others just as plainly speak of destruction, death, perishing, and final consumption (Matt 10:28; Rom 6:23; Mal 4:1–3). The biblical use of “eternal” often names the irrevocable outcome rather than the duration of the process itself (Heb 6:2; 9:12), allowing destruction to be eternal in consequence without requiring endless experience. Taken together, these strands permit—without demanding—the possibility that some souls persist under judgment while others, after proportionate punishment, finally cease to exist. Such a synthesis honors the full range of scriptural witness, preserves moral proportionality, and avoids importing assumptions about innate immortality not clearly taught in Scripture.

What Scripture does make clear is that eternal life consists in communion with God, and that exclusion from God’s presence constitutes true death and destruction. Whether eternal conscious punishment or eventual annihilation is the more loving outcome remains opaque to human judgment. What is incontrovertible, however, is that Hell’s reality is ever-enduring, that it was prepared for Satan and the demons, that some humans will freely reject God and thus justly enter it, and that whatever form judgment finally takes, it will be perfectly just and wholly consistent with the love and mercy God never ceases to embody.

Wrath as the Truthful Shape of Holy-Love

Wrath is not a contradiction of love, nor a lapse in divine patience, nor a suspension of mercy. It is one of holy-love’s necessary and truthful forms when love encounters reality as it actually is. Love does not float above moral history; it meets persons and communities within the concrete conditions their choices have created. When love encounters openness, it heals. When it encounters distortion, it exposes. When it encounters violence, it resists. When it encounters settled destruction, it judges. In every case, the motive remains the same: holy-love seeking the good of all it touches.

Love, in its multifarious expressions, invites and waits, but it also protects and intervenes. Depth-love bears with extraordinary patience, refusing to abandon even the one who wounds. Breadth-love safeguards those endangered by another’s will, refusing to allow harm to spread unchecked. Wrath arises precisely where these two movements converge—where patience for the perpetrator must give way to protection for the vulnerable, and where truth must interrupt a trajectory that would otherwise consume both victim and offender alike.

Wrath, then, is not divine temper but moral clarity. It is goodness refusing to collude with destruction. It is truth unveiling what has been hidden in darkness. It is love drawing a boundary where continued permission would itself become cruelty. Wrath does not negate freedom; it honors freedom’s weight by allowing choices to reach their proper moral disclosure. What love will not do is pretend that evil is harmless, temporary, or unreal.

In this sense, wrath is a severe mercy. It exposes lies before they metastasize. It restrains violence before it multiplies. It shortens the reach of corruption and hastens the moment of truth. Even when judgment is final, love has not ceased; it remains what it has always been. The pain experienced by the resistant soul testifies not to a change in God, but to the settled posture of the creature toward the unchanging radiance of holy-love.

Wrath is therefore not the dark underside of grace but its truthful contour in a fractured world. It reveals the moral seriousness of God’s love, the luminous integrity of His holiness, and the unwavering consistency of His character. The same radiant holiness that creates and sustains all things also confronts what destroys them—not because God delights in judgment, but because love, if it is truly love, must refuse to abandon the good.

In this way, wrath belongs within holiness, not against it. It is holy-love standing fully revealed in a world where love must sometimes wound in order to heal, resist in order to protect, and judge in order to remain faithful to the good it eternally seeks.

Scripture Support for the Above (NASB)

Ps 119:68 — You are good and do good; Teach me Your statutes.

John 14:6 — Jesus *said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but through Me.”

Rom 15:30 — Now I urge you, brethren, by our Lord Jesus Christ and by the love of the Spirit, to strive together with me in your prayers to God for me,

Deut 6:4 — “Hear, O Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord is one!”

John 10:30 — “I and the Father are one.”

Num 23:19 — “God is not a man, that He should lie, Nor a son of man, that He should repent; Has He said, and will He not do it? Or has He spoken, and will He not make it good?”

Jas 1:17 — Every good thing given and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shifting shadow.

Gen 1:31 — God saw all that He had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.

Ps 145:9 — The Lord is good to all, And His mercies are over all His works.

John 1:14 — And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory, glory as of the only begotten from the Father, full of grace and truth.

Rev 19:11 — And I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse, and He who sat on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and wages war.

Col 1:16–17 — For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things have been created through Him and for Him. He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together.

Heb 1:3 — And He is the radiance of His glory and the exact representation of His nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power. When He had made purification of sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high,

Isa 6:3 — And one called out to another and said, “Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord of hosts, The whole earth is full of His glory.”

Ps 89:14 — Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne; Lovingkindness and truth go before You.

1 John 4:8 — The one who does not love does not know God, for God is love.

Rom 11:36 — For from Him and through Him and to Him are all things. To Him be the glory forever. Amen.

Ps 97:10 — Hate evil, you who love the Lord, Who preserves the souls of His godly ones; He delivers them from the hand of the wicked.

Hab 1:13 — Your eyes are too pure to approve evil, And You can not look on wickedness with favor. Why do You look with favor On those who deal treacherously? Why are You silent when the wicked swallow up Those more righteous than themselves?

Ps 82:3–4 — Vindicate the weak and fatherless; Do justice to the afflicted and destitute. Rescue the weak and needy; Deliver them out of the hand of the wicked.

John 3:19–21 — “This is the judgment, that the Light has come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil. For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear that his deeds will be exposed. But he who practices the truth comes to the Light, so that his deeds may be manifested as having been wrought in God.”

Eph 5:11–13 — Do not participate in the unfruitful deeds of darkness, but instead even expose them; for it is disgraceful even to speak of the things which are done by them in secret. But all things become visible when they are exposed by the light, for everything that becomes visible is light.

Ezek 18:23 — “Do I have any pleasure in the death of the wicked,” declares the Lord God, “rather than that he should turn from his ways and live?”

Ezek 33:11 — “Say to them, ‘As I live!’ declares the Lord God, ‘I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that the wicked turn from his way and live. Turn back, turn back from your evil ways! Why then will you die, O house of Israel?’”

Prov 13:24 — He who withholds his rod hates his son, But he who loves him disciplines him diligently.

Heb 12:6 — For those whom the Lord loves He disciplines, And He scourges every son whom He receives.”

Ps 103:8–10 — The Lord is compassionate and gracious, Slow to anger and abounding in lovingkindness. He will not always strive with us, Nor will He keep His anger forever. He has not dealt with us according to our sins, Nor rewarded us according to our iniquities.

Lam 3:31–33 — For the Lord will not reject forever, For if He causes grief, Then He will have compassion According to His abundant lovingkindness. For He does not afflict willingly Or grieve the sons of men.

Mal 3:6 — “For I, the Lord, do not change; therefore you, O sons of Jacob, are not consumed.”

John 3:20 — “For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear that his deeds will be exposed.”

Isa 6:5 — Then I said, “Woe is me, for I am ruined! Because I am a man of unclean lips, And I live among a people of unclean lips; For my eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts.”

2 Cor 3:18 — But we all, with unveiled face, beholding as in a mirror the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from glory to glory, just as from the Lord, the Spirit.

Rom 1:21–25 — For even though they knew God, they did not honor Him as God or give thanks, but they became futile in their speculations, and their foolish heart was darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the incorruptible God for an image in the form of corruptible man and of birds and four-footed animals and crawling creatures. Therefore God gave them over in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, so that their bodies would be dishonored among them. For they exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever. Amen.

Rom 1:29–32 — being filled with all unrighteousness, wickedness, greed, evil; full of envy, murder, strife, deceit, malice; they are gossips, slanderers, haters of God, insolent, arrogant, boastful, inventors of evil, disobedient to parents, without understanding, untrustworthy, unloving, unmerciful; and although they know the ordinance of God, that those who practice such things are worthy of death, they not only do the same, but also give hearty approval to those who practice them.

Jas 3:14–16 — But if you have bitter jealousy and selfish ambition in your heart, do not be arrogant and so lie against the truth. This wisdom is not that which comes down from above, but is earthly, natural, demonic. For where jealousy and selfish ambition exist, there is disorder and every evil thing.

Deut 30:19 — “I call heaven and earth to witness against you today, that I have set before you life and death, the blessing and the curse. So choose life in order that you may live, you and your descendants,”

Jas 1:14–15 — But each one is tempted when he is carried away and enticed by his own lust. Then when lust has conceived, it gives birth to sin; and when sin is accomplished, it brings forth death.

Gen 3:17–19 — Then to Adam He said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten from the tree about which I commanded you, saying, ‘You shall not eat from it’; Cursed is the ground because of you; In toil you will eat of it All the days of your life. Both thorns and thistles it shall grow for you; And you will eat the plants of the field; By the sweat of your face You will eat bread, Till you return to the ground, Because from it you were taken; For you are dust, And to dust you shall return.”

Rom 8:20–22 — For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation groans and suffers the pains of childbirth together until now.

Hos 4:1–3 — Listen to the word of the Lord, O sons of Israel, For the Lord has a case against the inhabitants of the land, Because there is no faithfulness or kindness Or knowledge of God in the land. There is swearing, deception, murder, stealing and adultery. They employ violence, so that bloodshed follows bloodshed. Therefore the land mourns, And everyone who lives in it languishes Along with the beasts of the field and the birds of the sky, And also the fish of the sea disappear.

Rev 11:18 — “And the nations were enraged, and Your wrath came, and the time came for the dead to be judged, and the time to reward Your bond-servants the prophets and the saints and those who fear Your name, the small and the great, and to destroy those who destroy the earth.”

Nah 1:2–3 — A jealous and avenging God is the Lord; The Lord is avenging and wrathful. The Lord takes vengeance on His adversaries, And He reserves wrath for His enemies. The Lord is slow to anger and great in power, And the Lord will by no means leave the guilty unpunished. In whirlwind and storm is His way, And clouds are the dust beneath His feet.

Hos 13:8 — I will encounter them like a bear robbed of her cubs, And I will tear open their chests; There I will also devour them like a lioness, As a wild beast would tear them.

Heb 12:11 — All discipline for the moment seems not to be joyful, but sorrowful; yet to those who have been trained by it, afterwards it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness.

Prov 20:30 — Stripes that wound scour away evil, And strokes reach the innermost parts.

Ps 103:8–9 — The Lord is compassionate and gracious, Slow to anger and abounding in lovingkindness. He will not always strive with us, Nor will He keep His anger forever.

Ezek 18:32 — “For I have no pleasure in the death of anyone who dies,” declares the Lord God. “Therefore, repent and live.”

Exod 34:6 — Then the Lord passed by in front of him and proclaimed, “The Lord, the Lord God, compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in lovingkindness and truth;”

Ps 145:8 — The Lord is gracious and merciful; Slow to anger and great in lovingkindness.

2 Pet 3:9 — The Lord is not slow about His promise, as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing for any to perish but for all to come to repentance.

Ps 72:4 — May he vindicate the afflicted of the people, Save the children of the needy And crush the oppressor.

Matt 5:44–45 — “But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for He causes His sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.”

Ps 34:18 — The Lord is near to the brokenhearted And saves those who are crushed in spirit.

Luke 15:11–32 — (The Parable of the Prodigal Son – full text omitted for brevity; it illustrates God's pursuit of the lost.)

Col 1:24 — Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I do my share on behalf of His body, which is the church, in filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions.

Rom 2:4 — Or do you think lightly of the riches of His kindness and tolerance and patience, not knowing that the kindness of God leads you to repentance?

Gal 6:2 — Bear one another’s burdens, and thereby fulfill the law of Christ.

Rom 8:26 — In the same way the Spirit also helps our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we should, but the Spirit Himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words;

Matt 5:39–44 — “But I say to you, do not resist an evil person; but whoever slaps you on your right cheek, turn the other to him also... But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,”

Prov 22:3 — The prudent sees the evil and hides himself, But the naive go on, and are punished for it.

Prov 27:12 — A prudent man sees evil and hides himself, The naive proceed and pay the penalty.

Isa 53:4–5 — Surely our griefs He Himself bore, And our sorrows He carried; Yet we ourselves esteemed Him stricken, Smitten of God, and afflicted. But He was pierced through for our transgressions, He was crushed for our iniquities; The chastening for our well-being fell upon Him, And by His scourging we are healed.

Rom 8:17 — and if children, heirs also, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, if indeed we suffer with Him so that we may also be glorified with Him.

Ps 91:14–16 — “Because he has loved Me, therefore I will deliver him; I will set him securely on high, because he has known My name. He will call upon Me, and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble; I will rescue him and honor him. With a long life I will satisfy him And let him see My salvation.”

Acts 4:29–31 — “And now, Lord, take note of their threats, and grant that Your bond-servants may speak Your word with all confidence, while You extend Your hand to heal, and signs and wonders take place through the name of Your holy servant Jesus.” And when they had prayed, the place where they had gathered together was shaken, and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak the word of God with boldness.

Ps 11:5–7 — The Lord tests the righteous and the wicked, And the one who loves violence His soul hates. Upon the wicked He will rain snares; Fire and brimstone and burning wind will be the portion of their cup. For the Lord is righteous, He loves righteousness; The upright will behold His face.

Rom 8:28 — And we know that God causes all things to work together for good to those who love God, to those who are called according to His purpose.

Gen 50:20 — “As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good in order to bring about this present result, to preserve many people alive.”

Matt 18:34–35 — “And his lord, moved with anger, handed him over to the torturers until he should repay all that was owed him. My heavenly Father will also do the same to you, if each of you does not forgive his brother from your heart.”

Luke 6:27–28 — “But I say to you who hear, love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.”

Rom 12:20–21 — “But if your enemy is hungry, feed him, and if he is thirsty, give him a drink; for in so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

Ezek 18:23 — “Do I have any pleasure in the death of the wicked,” declares the Lord God, “rather than that he should turn from his ways and live?”

2 Cor 7:10 — For godly sorrow produces repentance leading to salvation, not to be regretted; but the sorrow of the world produces death.

Acts 17:28 — for in Him we live and move and exist, as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we also are His children.’

Ps 139:7–10 — Where can I go from Your Spirit? Or where can I flee from Your presence? If I ascend to heaven, You are there; If I make my bed in Sheol, behold, You are there. If I take the wings of the dawn, If I dwell in the remotest part of the sea, Even there Your hand will lead me, And Your right hand will lay hold of me.

1 Cor 6:19 — Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, whom you have from God, and that you are not your own?

Rom 1:18–21 — For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men who suppress the truth in unrighteousness, because that which is known about God is evident within them; for God made it evident to them. For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes, His eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly seen, being understood through what has been made, so that they are without excuse. For even though they knew God, they did not honor Him as God or give thanks, but they became futile in their speculations, and their foolish heart was darkened.

John 16:8 — “And He, when He comes, will convict the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment;”

Prov 16:9 — The mind of man plans his way, But the Lord directs his steps.

Prov 19:21 — Many plans are in a man’s heart, But the counsel of the Lord will stand.

Hos 2:6–7 — “Therefore, behold, I will hedge up her way with thorns, And I will build a wall against her so that she cannot find her paths. She will pursue her lovers, but she will not overtake them; And she will seek them, but will not find them. Then she will say, ‘I will go back to my first husband, For it was better for me then than now!’”

Luke 8:17 — “For nothing is hidden that will not become evident, nor anything secret that will not be known and come to light.”

1 Tim 5:24 — The sins of some men are quite evident, going before them to judgment; for others, their sins follow after.

Jer 17:9 — “The heart is more deceitful than all else And is desperately sick; Who can understand it?”

Rom 1:24–28 — Therefore God gave them over in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, so that their bodies would be dishonored among them. For they exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever. Amen. For this reason God gave them over to degrading passions; for their women exchanged the natural function for that which is unnatural, and in the same way also the men abandoned the natural function of the woman and burned in their desire toward one another, men with men committing indecent acts and receiving in their own persons the due penalty of their error. And just as they did not see fit to acknowledge God any longer, God gave them over to a depraved mind, to do those things which are not proper,

Rom 13:3–4 — For rulers are not a cause of fear for good behavior, but for evil. Do you want to have no fear of authority? Do what is good and you will have praise from the same; for it is a minister of God to you for good. But if you do what is evil, be afraid; for it does not bear the sword for nothing; for it is a minister of God, an avenger who brings wrath on the one who practices evil.

Isa 1:18 — “Come now, and let us reason together,” Says the Lord, “Though your sins are as scarlet, They will be as white as snow; Though they are red like crimson, They will be like wool.”

Ps 94:1–2 — O Lord, God of vengeance, God of vengeance, shine forth! Rise up, O Judge of the earth, Render recompense to the proud.

Prov 14:16 — A wise man is cautious and turns away from evil, But a fool is arrogant and careless.

Gen 6:5–7 — Then the Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great on the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. The Lord was sorry that He had made man on the earth, and He was grieved in His heart. The Lord said, “I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the land, from man to animals to creeping things and to birds of the sky; for I am sorry that I have made them.”

Jas 1:13 — Let no one say when he is tempted, “I am being tempted by God”; for God cannot be tempted by evil, and He Himself does not tempt anyone.

Rom 9:17–18 — For the Scripture says to Pharaoh, “For this very purpose I raised you up, to demonstrate My power in you, and that My name might be proclaimed throughout the whole earth.” So then He has mercy on whom He desires, and He hardens whom He desires.

Prov 16:4 — The Lord has made everything for its own purpose, Even the wicked for the day of evil.

Isa 55:6–7 — Seek the Lord while He may be found; Call upon Him while He is near. Let the wicked forsake his way And the unrighteous man his thoughts; And let him return to the Lord, And He will have compassion on him, And to our God, For He will abundantly pardon.

Heb 3:12–13 — Take care, brethren, that there not be in any one of you an evil, unbelieving heart that falls away from the living God. But encourage one another day after day, as long as it is still called “Today,” so that none of you will be hardened by the deceitfulness of sin.

Exod 8:15 — But when Pharaoh saw that there was relief, he hardened his heart and did not listen to them, as the Lord had said.

Exod 8:32 — But Pharaoh hardened his heart this time also, and he did not let the people go.

Exod 9:34–35 — But when Pharaoh saw that the rain and the hail and the thunder had ceased, he sinned again and hardened his heart, he and his servants. Pharaoh’s heart was hardened, and he did not let the sons of Israel go, just as the Lord had spoken through Moses.

Ps 37:12–13 — The wicked plots against the righteous And gnashes at him with his teeth. The Lord laughs at him, For He sees his day is coming.

Luke 13:1–5 — Now on the same occasion there were some present who reported to Him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices. And Jesus said to them, “Do you suppose that these Galileans were greater sinners than all other Galileans because they suffered this fate? I tell you, no, but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. Or do you suppose that those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them were worse culprits than all the men who live in Jerusalem? I tell you, no, but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

Rom 2:5 — But because of your stubbornness and unrepentant heart you are storing up wrath for yourself in the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God,

Prov 11:21 — Assuredly, the evil man will not go unpunished, But the descendants of the righteous will be delivered.

Eccl 8:11–13 — Because the sentence against an evil deed is not executed quickly, therefore the hearts of the sons of men among them are given fully to do evil. Although a sinner does evil a hundred times and may lengthen his life, still I know that it will be well for those who fear God, who fear Him openly. But it will not be well for the evil man and he will not lengthen his days like a shadow, because he does not fear God.

Luke 12:2–3 — “But there is nothing covered up that will not be revealed, and hidden that will not be known. Accordingly, whatever you have said in the dark will be heard in the light, and what you have whispered in the inner rooms will be proclaimed upon the housetops.”

Acts 17:30 — “Therefore having overlooked the times of ignorance, God is now declaring to men that all people everywhere should repent,”

Rom 1:32 — and although they know the ordinance of God, that those who practice such things are worthy of death, they not only do the same, but also give hearty approval to those who practice them.

Heb 12:29 — for our God is a consuming fire.

Rev 2:21 — ‘I gave her time to repent, and she does not want to repent of her immorality.’

Prov 3:11–12 — My son, do not reject the discipline of the Lord Or loathe His reproof, For whom the Lord loves He reproves, Even as a father corrects the son in whom he delights.

Mic 6:8 — He has told you, O man, what is good; And what does the Lord require of you But to do justice, to love kindness, And to walk humbly with your God?

Gen 9:6 — “Whoever sheds man’s blood, By man his blood shall be shed, For in the image of God He made man.”

Luke 12:47–48 — “And that slave who knew his master’s will and did not get ready or act in accord with his will, will receive many lashes, but the one who did not know it, and committed deeds worthy of a flogging, will receive but few. From everyone who has been given much, much will be required; and to whom they entrusted much, of him they will ask all the more.”

Heb 9:27 — And inasmuch as it is appointed for men to die once and after this comes judgment,

1 Cor 15:42–44 — So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown a perishable body, it is raised an imperishable body; it is sown in dishonor, it is raised in glory; it is sown in weakness, it is raised in power; it is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body.

Rev 21:23 — And the city has no need of the sun or of the moon to shine on it, for the glory of God has illumined it, and its lamp is the Lamb.

Ps 139:8 — If I ascend to heaven, You are there; If I make my bed in Sheol, behold, You are there.

John 5:29 — and will come forth; those who did the good deeds to a resurrection of life, those who committed the evil deeds to a resurrection of judgment.

2 Thess 1:8–9 — dealing out retribution to those who do not know God and to those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power,

Matt 25:41 — “Then He will also say to those on His left, ‘Depart from Me, accursed ones, into the eternal fire which has been prepared for the devil and his angels;”

Rev 20:11–15 — Then I saw a great white throne and Him who sat upon it, from whose presence earth and heaven fled away, and no place was found for them. And I saw the dead, the great and the small, standing before the throne, and books were opened; and another book was opened, which is the book of life; and the dead were judged from the things which were written in the books, according to their deeds. And the sea gave up the dead which were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead which were in them; and they were judged, every one of them according to their deeds. Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire. And if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire.

John 3:36 — “He who believes in the Son has eternal life; but he who does not obey the Son will not see life, but the wrath of God abides on him.”

Gal 6:7–8 — Do not be deceived, God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, this he will also reap. For the one who sows to his own flesh will from the flesh reap corruption, but the one who sows to the Spirit will from the Spirit reap eternal life.

Rom 2:6–8 — who will render to each person according to his deeds: to those who by perseverance in doing good seek for glory and honor and immortality, eternal life; but to those who are selfishly ambitious and do not obey the truth, but obey unrighteousness, wrath and indignation.

Rev 19:2 — “because His judgments are true and righteous; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and He has avenged the blood of His bond-servants on her.”

Isa 30:18 — Therefore the Lord longs to be gracious to you, And therefore He waits on high to have compassion on you. For the Lord is a God of justice; How blessed are all those who long for Him.

John 3:19–20 — “This is the judgment, that the Light has come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil. For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear that his deeds will be exposed.”

Matt 25:46 — “These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

Mal 4:1 — “For behold, the day is coming, burning like a furnace; and all the arrogant and every evildoer will be chaff; and the day that is coming will set them ablaze,” declares the Lord of hosts, “so that it will leave them neither root nor branch.”

1 Tim 6:16 — who alone possesses immortality and dwells in unapproachable light, whom no man has seen or can see. To Him be honor and eternal dominion! Amen.

John 17:3 — “This is eternal life, that they may know You, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom You have sent.”

2 Thess 1:9 — These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power,

Isa 55:8–9 — “For My thoughts are not your thoughts, Nor are your ways My ways,” declares the Lord. “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, So are My ways higher than your ways And My thoughts than your thoughts.”

Mark 9:48 — where their worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched.

John 5:40 — and you are unwilling to come to Me so that you may have life.

Rev 15:3–4 — And they *sang the song of Moses, the bond-servant of God, and the song of the Lamb, saying, “Great and marvelous are Your works, O Lord God, the Almighty; Righteous and true are Your ways, King of the nations! Who will not fear, O Lord, and glorify Your name? For You alone are holy; For all the nations will come and worship before You, For Your righteous acts have been revealed.”

Jer 17:10 — “I, the Lord, search the heart, I test the mind, Even to give to each man according to his ways, According to the results of his deeds.”

Hos 14:4 — “I will heal their apostasy, I will love them freely, For My anger has turned away from them.”

Ps 18:7–8 — Then the earth shook and quaked; And the foundations of the mountains were trembling And were shaken, because He was angry. Smoke went up out of His nostrils, And fire from His mouth devoured; Coals were kindled by it.

Rom 2:5–6 — But because of your stubbornness and unrepentant heart you are storing up wrath for yourself in the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God, who will render to each person according to his deeds:

1 Cor 13:6 — does not rejoice in unrighteousness, but rejoices with the truth;

Ps 82:4 — Rescue the weak and needy; Deliver them out of the hand of the wicked.

Rom 5:8 — But God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us.

Prov 24:11–12 — Deliver those who are being taken away to death, And those who are staggering to slaughter, Oh hold them back. If you say, “See, we did not know this,” Does He not consider it who weighs the hearts? And does He not know it who keeps your soul? And will He not render to man according to his work?

Eccl 3:3 — A time to kill and a time to heal; A time to tear down and a time to build up.

Hab 1:13 — Your eyes are too pure to approve evil, And You can not look on wickedness with favor. Why do You look with favor On those who deal treacherously? Why are You silent when the wicked swallow up Those more righteous than themselves?

Isa 5:20 — Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil; Who substitute darkness for light and light for darkness; Who substitute bitter for sweet and sweet for bitter!

Prov 27:6 — Faithful are the wounds of a friend, But deceitful are the kisses of an enemy.

Rom 2:2 — And we know that the judgment of God rightly falls upon those who practice such things.

Rom 11:22 — Behold then the kindness and severity of God; to those who fell, severity, but to you, God’s kindness, if you continue in His kindness; otherwise you also will be cut off.

Rev 15:3 — And they *sang the song of Moses, the bond-servant of God, and the song of the Lamb, saying, “Great and marvelous are Your works, O Lord God, the Almighty; Righteous and true are Your ways, King of the nations!”