Scripture Use in LUMEN: From Proof Texts to Proof Clouds

by Dr. Peter A. Kerr

LUMEN begins with a deep reverence for Scripture. The Bible is received not as a problem to be managed or a quarry for argumentative ammunition, but as a fulsome and authoritative witness to God’s self-revelation in history, culminating in Jesus Christ. Scripture is not subordinated to philosophy, experience, or theology. It is allowed to speak, to converge, and to form us over time. It is the infallible Word of God.

While some divisions arise in the Church between those who hold a high view of Scripture and those who do not, other divisions occur even among those who affirm its full authority. Where Scripture is silent, people have often filled in gaps with confident human reasoning, or when there is a difficult issue that has nuance throughout Scripture people try to simplify by elevating a single verse and declaring it alone should be seen as authoritative. Much division arises not from Scripture itself, but from how Scripture is used.

The goal of LUMEN, which is to accurately articulate what Christianity was meant to be, is prima facia audacious. However, it is “child’s play” for the Holy Spirit. Thus, when I became convinced God was calling me to this task, I knew I had to pray and listen as much as I had to think.

Having been trained at a Bible-believing conservative seminary (my MDIV is from Asbury Theological Seminary), I insisted upon anchoring everything in Scripture. Early in the development of LUMEN, however, when I asked God for clear proof texts for every claim I had not seen before, I was met with denial. God refused to provide short, decisive verses that could be cited to settle every doctrine I was illuminating beyond dispute. I was then led to understand “proof texts” are often part of the problem rather than the solution.

Throughout Christian history, entire theological systems have been constructed from isolated phrases removed from their literary, canonical, and relational contexts. A single line is elevated, abstracted, and pressed into service as a controlling axiom. Other texts are then forced to conform, minimized, or explained away. The result has frequently been doctrinal rigidity, mutual suspicion, and the splintering of Christ’s body.

Scripture was not given to function this way.

The biblical canon is not a list of propositions. It is a multifaceted witness composed of narrative, law, prophecy, poetry, wisdom literature, gospel, epistle, and apocalypse. God did not reveal Himself in sound bites, but across centuries of lived relationship with a people.

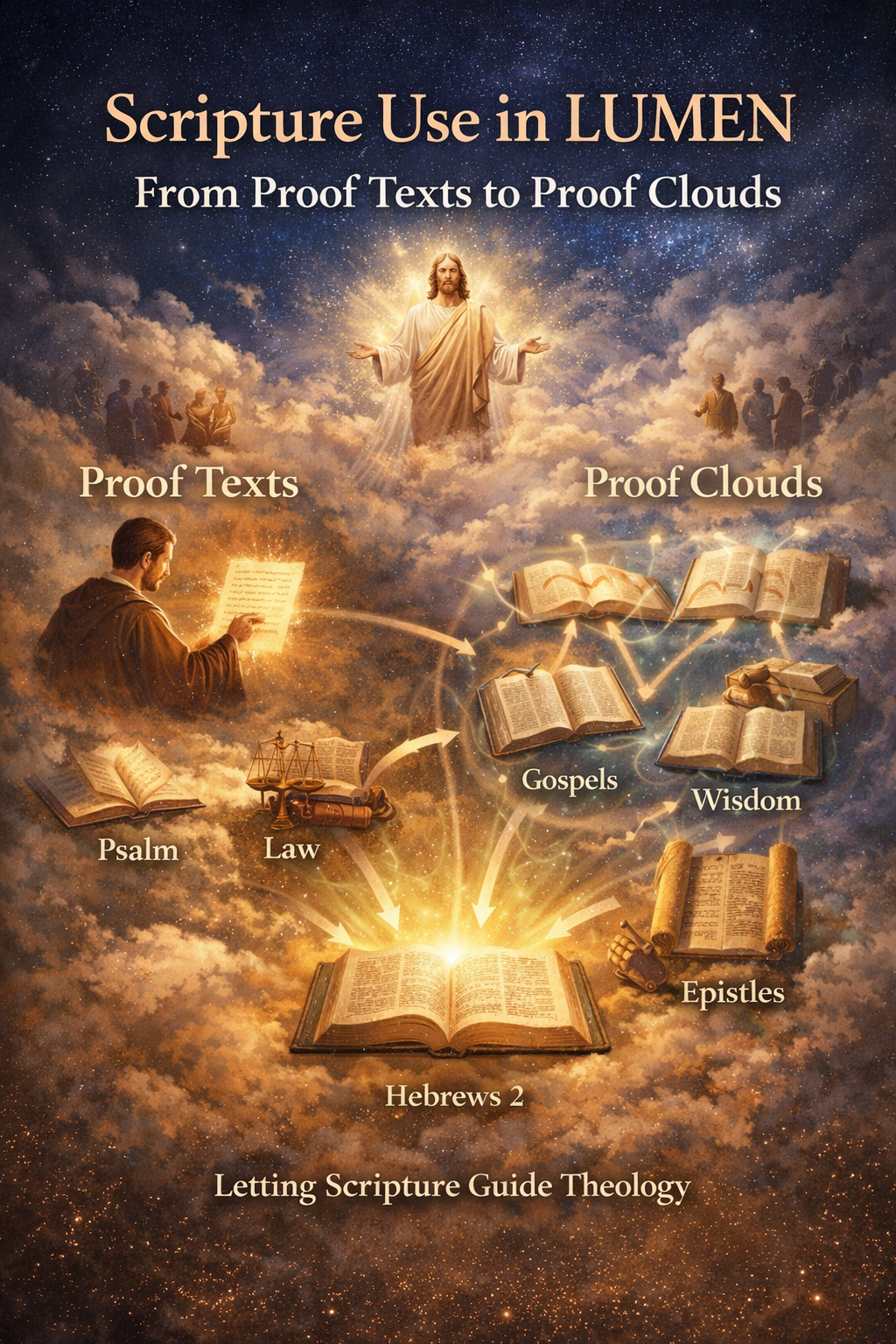

LUMEN therefore employs what might be called “proof clouds” rather than proof texts. A proof cloud is a convergence of many passages, across different authors, genres, and covenants, all pointing in the same theological direction. No single verse carries the full weight. Instead, the cumulative witness of Scripture forms a coherent pattern.

This approach values breadth and depth:

• Breadth, by attending to the whole canon rather than privileging a narrow slice

• Depth, by allowing repeated themes to clarify meaning over time

A doctrine is treated as sound not because one verse appears to state it baldly, but because Scripture as a whole leans that way—again and again, from multiple angles. The strength of a theological claim increases when:

• Both Old and New Testament texts converge

• Narrative and instruction support one another

• Prose and poetry (including psalms and wisdom literature)

• Theology emerges naturally from repeated biblical patterns

This is how Scripture itself teaches us to read Scripture (Lk 24:27, 44, cf. Acts17:11). LUMEN does not deny that Scripture teaches truth clearly; it denies that truth is best heard when Scripture is reduced to fragments rather than received as a whole.

This rejection of “proof texts” is also not a rejection of all creeds and systematizations. The Body of Christ may indeed come to a consensus position and encapsulate it in a statement. In fact, the best of these creeds and confessions did not arise from proof-texting but actually already applied the “proof-cloud” reasoning. They sought to summarize Scripture’s teaching, not replace it.

Genre and audience matter

LUMEN insists that Scripture must always be read according to its genre. Poetry should not be treated as technical prose. Narrative should not be flattened into abstract doctrine. Wisdom literature speaks differently than law. Apocalyptic imagery cannot be read as straightforward journalistic prediction. The Bible loses its intended meaning when genre is ignored in the rush for certainty. Respecting genre does not weaken biblical authority. It honors it.

Equally important is the question of audience. Scripture addresses specific people in specific covenantal moments. Some texts are spoken to Israel under the law. Others to exiles, priests, kings, disciples, persecuted churches, or fractured communities. Commands, warnings, promises, and descriptions must be read in light of who is being addressed and why.

LUMEN resists the temptation to universalize every line without discernment. It also resists the opposite temptation to relativize Scripture away. Faithful interpretation requires careful attention to both continuity and development within the biblical story.

Letting Scripture Lead Theology

At the heart of LUMEN’s approach is a simple commitment: Scripture must be allowed to guide theology, not the other way around. Faithful teachers rightly build on the work of those who came before them, carefully documenting sources and refining ideas with intellectual discipline. Such continuity is a gift to the church. Yet over time, this incremental method can quietly harden into an assumption—that theology advances only by small adjustments within inherited systems. When that happens, Scripture may be asked to fill the gaps of a framework rather than to question it, and silence can be mistaken for permission.

When theological systems are extended beyond what Scripture clearly reveals, errors need not arise from bad intent. They arise from momentum. Small misalignments, repeated and reinforced, can compound across generations until the tradition becomes confident in conclusions Scripture never explicitly taught. At such moments, the church often struggles to see beyond its own settled categories.

This is why God, in His mercy, raises up apostles and prophets—biblically understood as those who faithfully declare and re-articulate His Word—not to discard the labor of teachers, but to re-anchor the church in what He has actually revealed. Their role is not novelty but fidelity: to call God’s people back to the living Word, to clear away accumulated assumptions, and to set the path straight again by the light of Scripture itself.

Theology especially becomes distorted when we begin with a system and then recruit verses to support it. Scripture is not a courtroom witness to be cross-examined. It is a living testimony that shapes our vision of God, humanity, holiness, freedom, judgment, and love.

Correctly discerning the Word of God requires patience. It often resists quick answers. We must not overlook but rather welcome tension where Scripture itself holds tension. We must value coherence over cleverness and unity over domination.

Most of all, we must keep theology anchored to the God who reveals Himself not merely in words, but in relationship—ultimately and decisively in Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh. Any theology that says God the Father acts entirely different than God the Son or God the Spirit has violated the core belief that God is not divided but one—what theology calls a “simple” essence: God is holy.

LUMEN does not claim to end theological disagreement. It proposes a way of listening that is more faithful, more communal, and more aligned with the nature of Scripture itself. It proposes that starting with who God is and why He created is the most faithful way of creating theology—it is far better than starting with the problem of how humans deal with sin or get saved. The Hebrew in Genesis 1:1 starts with two words: “Beginning” to say the story starts then “God” to name the main actor and the real point of the theology.

If Scripture is truly a gift meant to form a people of holy love, then how we read it matters just as much as what we say it teaches. Let us read it faithfully, fully, and fearlessly as we discover what God meant for Christianity to be.

Supporting Scripture (in NASB)

Luke 24:27 "Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures."

Luke 24:44 "Now He said to them, 'These are My words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things which are written about Me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.'"

Acts 17:11 "Now these were more noble-minded than those in Thessalonica, for they received the word with great eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see whether these things were so."

Genesis 1:26–28 "Then God said, 'Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.' God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them. God blessed them; and God said to them, 'Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over every living thing that moves on the earth.'"

Psalm 8 (the psalm is referenced as a whole in poetic reflection on human dominion) "O LORD, our Lord, How majestic is Your name in all the earth, Who have displayed Your splendor above the heavens! From the mouth of infants and nursing babes You have established strength Because of Your adversaries, To make the enemy and the revengeful cease. When I consider Your heavens, the work of Your fingers, The moon and the stars, which You have ordained; What is man that You take thought of him, And the son of man that You care for him? Yet You have made him a little lower than God, And You crown him with glory and majesty! You make him to rule over the works of Your hands; You have put all things under his feet, All sheep and oxen, And also the beasts of the field, The birds of the heavens and the fish of the sea, Whatever passes through the paths of the seas. O LORD, our Lord, How majestic is Your name in all the earth!"

Matthew 6:9–10 "Pray, then, in this way: 'Our Father who is in heaven, Hallowed be Your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done, On earth as it is in heaven.'"

1 Corinthians 3:9 "For we are God’s fellow workers; you are God’s field, God’s building."

Romans 8:19–21 "For the anxious longing of the creation waits eagerly for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of Him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be set free from its slavery to corruption into the freedom of the glory of the children of God."

Hebrews 2 (explicitly links to Psalm 8, presenting Jesus as fulfilling humanity's role) (Key verses applying Psalm 8: Hebrews 2:6–9) "But one has testified somewhere, saying, 'WHAT IS MAN, THAT YOU REMEMBER HIM? OR THE SON OF MAN, THAT YOU ARE CONCERNED ABOUT HIM? YOU HAVE MADE HIM FOR A LITTLE WHILE LOWER THAN THE ANGELS; YOU HAVE CROWNED HIM WITH GLORY AND HONOR, AND HAVE APPOINTED HIM OVER THE WORKS OF YOUR HANDS; YOU HAVE PUT ALL THINGS IN SUBJECTION UNDER HIS FEET.' For in subjecting all things to him, He left nothing that is not subject to him. But now we do not yet see all things subjected to him. But we do see Him who was made for a little while lower than the angels, namely, Jesus, because of the suffering of death crowned with glory and honor, so that by the grace of God He might taste death for everyone."

Genesis 1:1 "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth."

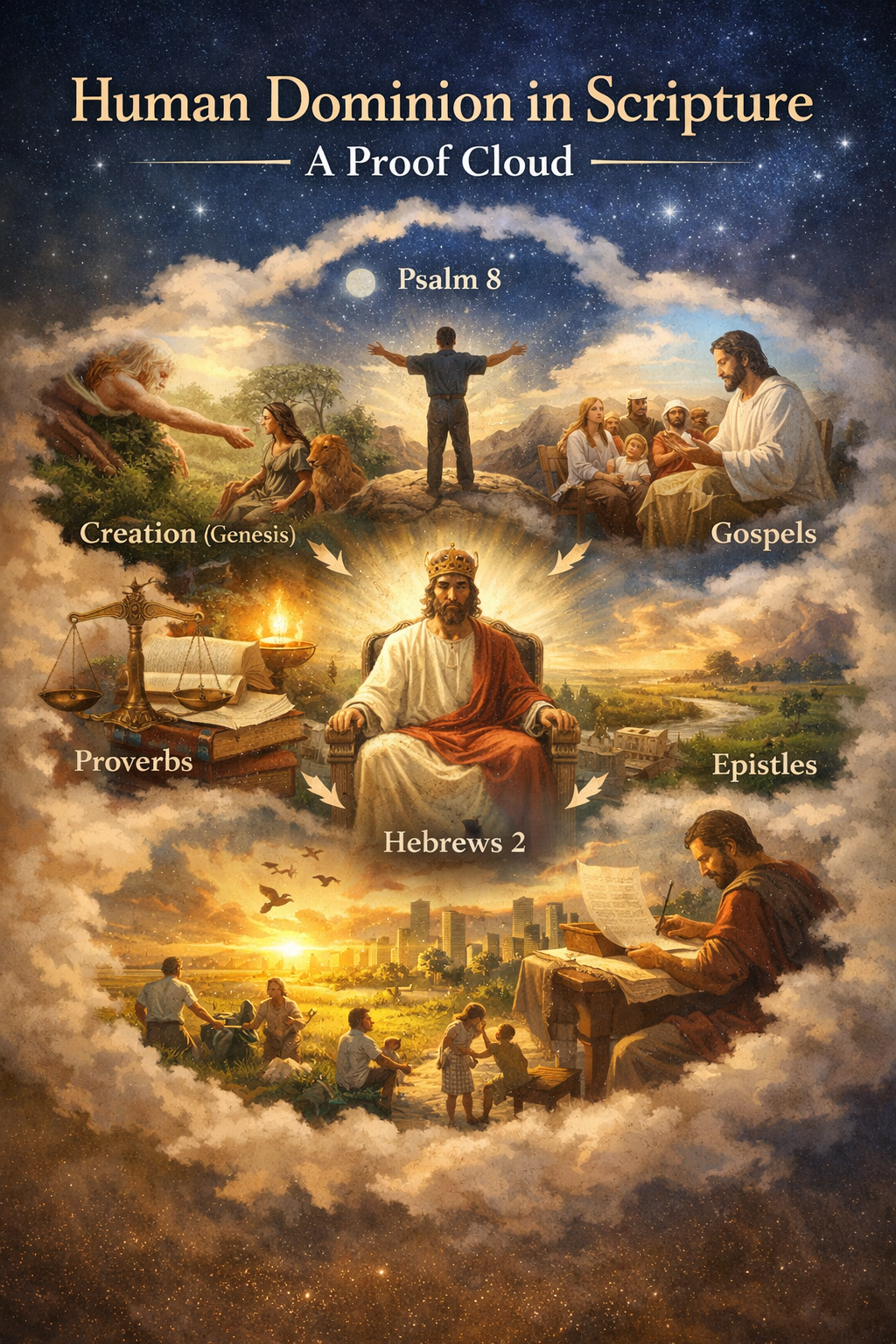

A Proof Cloud in Practice — Human Dominion in Scripture

One example of how LUMEN reads Scripture through “proof clouds” rather than proof texts can be seen in the biblical theme of human dominion. No single verse carries the doctrine. Instead, a broad convergence of Scripture reveals a coherent pattern.

The cloud begins at creation.

Genesis 1:26–28 presents humanity as made in God’s image and entrusted with dominion over the earth. This dominion is not framed as exploitation or control, but as stewardship exercised under God’s authority. Humanity is given real agency within creation, not as a rival to God, but as His appointed representative.

Psalm 8 reflects on this same reality in poetic form. Humanity is described as crowned with glory and honor, placed “over the works of Your hands,” with all things set under human feet. The psalm does not revoke Genesis; it worshipfully reaffirms it. Narrative and poetry speak with one voice.

The theme continues in the wisdom tradition. Proverbs assumes human responsibility, moral agency, and meaningful choice within God’s ordered world. Human decisions are portrayed as consequential, not illusory.

In the New Testament, this dominion is neither erased nor replaced. Jesus repeatedly treats human participation as real. He invites prayer not as information-sharing but as a means by which God’s will is enacted on earth (Matthew 6:9–10). The earth is portrayed as a domain where God’s reign is welcomed, not imposed.

Paul reinforces this participatory vision. Believers are described as “God’s fellow workers” (1 Corinthians 3:9), language that makes little sense if human agency is merely apparent. Creation itself is said to be waiting for the revealing of the children of God (Romans 8:19–21), suggesting that human redemption is tied to creation’s renewal.

Finally, Hebrews 2 explicitly links Psalm 8 to Jesus, presenting Him as the faithful human who fulfills humanity’s intended role without negating it. Dominion is not abolished in Christ; it is restored and rightly ordered. Notably, Scripture never presents human dominion as illusory, symbolic, or merely apparent—despite frequent opportunities to do so.

Taken together, these texts form a proof cloud:

• Creation narrative (Genesis)

• Worshipful reflection (Psalms)

• Moral wisdom (Proverbs)

• Teaching of Jesus (Gospels)

• Apostolic theology (Epistles)

No single verse establishes the doctrine alone. Yet the convergence is unmistakable. Scripture consistently portrays humanity as genuinely entrusted with responsibility within God’s world, a trust that grounds prayer, stewardship, moral accountability, and hope.

This is how Scripture teaches us to read Scripture—not by isolating a line, but by listening to the many voices that together testify to God’s intent.